Chick Corea Is the Well-Tempered Clavierist – Tom Moon

At 78, in the midst of a wave of creative activity that’s impressive even for him, the pianist is intensely focused on staying in tune—in every sense of that term

For most of its recent tour, the Chick Corea Trio has opened its concerts with a seemingly ordinary tuning ritual.

Corea plays a series of As in the piano’s middle register. Christian McBride adjusts his bass as needed. Brian Blade, drums impeccably pre-tuned, tests a few brush strokes on the snare drum. Business as usual.

And then Corea offers that same A 440 to the audience.

He politely requests that they sing an A back. After several more such exchanges, there comes a curveball: a short three-note phrase. As Corea repeats the phrase, he makes conductor-like gestures. The next one is more intricate—a ringtone from a galaxy with faster mental processing. This loses people. Chick Corea smiles a delighted evil-professor smile and keeps going, adding a tritone monkey wrench, upping the degree of difficulty.

It’s a little gimmicky, this call-and-response game. The performance equivalent of jumping jacks before gym class. But on the night I caught the group, at the Kimmel Center in Philadelphia, its effect was outsized. After the tuning, when the first plaintive rubato notes of “500 Miles High” arrived, the audience seemed alert and fully receptive, ready to listen, primed for something other than the usual “legend playing the greatest hits” experience.

Musicians rely on tuning to create a sense of unity on the bandstand. Corea’s tuning game widens the circle, luring concertgoers into the trio’s workspace, making them participants. In the age of 24/7 handheld distraction machines, it’s a gentle bit of subversion, an end run around attention deficit disorder.

“At first I did it for a lark,” Corea explains. “And then I found out that beyond just a fun moment we might have with the audience, it sets us up for great communication right at the beginning of the show.”

Blade goes further: “You know, people initially might be shy to sing out, if they’re alone. But they hear the whole room is doing it, and what a congregational beauty that brings. It makes everybody loosen up … Chick is all about engaging with people, and this opens the door and invites them to share in the experience.”

Sure enough, that’s what happens. For nearly two hours, the hall is a zone of active listening. The three musicians play at a hushed or moderate volume, Blade mostly on brushes, through a challenging program of Corea’s originals, standards, and Thelonious Monk tunes. They converse from the first theme statement to the last chord, following each other around blind-alley corners and down rickety unlit stairs, chasing dramatic extremes of soft and loud, density and spaciousness, tension and release.

Corea says his goal, particularly on the ballads, is to glimpse new possibilities of color and texture. “As a sonic person, an orchestrator, I find it incredibly interesting, and delicious actually, to have these three different timbres [piano, bass, drums] to work with. It’s a classic sound but it doesn’t have to be just that. We play with a lot of space—you have to become very sensitive to make each other sound good.”

Chick Corea is 78 years old. He has been cultivating this discourse—between himself, an astonishing list of collaborators, and the audiences for his varied projects—for more than six decades. At a time of life when most people are slowing down, Corea is in the midst of a furious creative outpouring. He’s released 13 records of new or live material since 2011. He’s toured around the world with several completely different projects, and has commissions lined up that will consume every scrap of “downtime” he might get in 2020.

Our conversation took place in a hotel suite overlooking Independence Hall in Philadelphia. The focal point of the room was a keyboard; Corea has been preparing to play his Piano Concerto with the Seattle and Portland Symphonies when the current trio tour ends. McBride says the pianist has been obsessive about practicing the work, and when I ask about it, Corea is blunt. “I wrote this piano concerto with a good spirit but never thought to myself that I’d be playing it with orchestras. So now I’m needing to learn it well enough so I don’t look like a jerk when I get there.”

He laughs in a hearty, contagious way, then abruptly pivots back to his concern. “No, I mean that. It’s written notes. I’ve got to play a certain amount of the written notes in order to make it sound like the piece I wrote. In order to let the orchestra know where I’m at.”

This is the only time over an extended conversation that Corea expresses anything resembling anxiety. He’s one of those lively intellects who leaps across disciplines to make a point—he invokes Nathaniel Hawthorne’s “The Great Stone Face” to answer a question about interacting with Herbie Hancock in a duo situation. As he speaks, it becomes clear that the nitty-gritty challenges of making music are way more important to him than any of the after-effects, the critical raves, or lifetime achievement awards. He’s wired for the moment, oriented in an almost obsessive way toward new creative endeavors. For him, everything lines up around a single overarching goal: communication.

JT: Do you sense, in the audiences at your shows, a difference in terms of attention since the smartphone came along? Is this a concern for artists who are focusing on interplay, often unscripted interplay?

As an artist I’ve learned what I think is the wisdom of putting those kinds of changes, like attention, on a lower mechanical level, in order to focus on the essential thing that happens in music between an artist and an audience. No matter what culture you’re in or what period of history, human beings communicating comes down to the same basic thing: the desire to get someone’s attention and to maintain his attention. For you to have an exchange that not only makes sense but is pleasurable is, I hate to throw out this word but I think it’s the correct one, “archetypical.” It’s built into the human way of living. The essential thing that happens in music is an element that was there from the beginning of time and will never change until the end of time. And that’s human spiritual contact.

Right, but as an improvising artist you have an unusual hill to climb: to involve listeners in your mostly abstract pursuit. How do you bring people into that?

Most of the audience, they’re not professionals. They maybe don’t recognize when we’re playing the melody from an original score and when we’re departing from it. A lot of people are surprised to learn that we’re playing on a form at all! They hear it as one endless meandering of notes. I never gear the performance so that people need to recognize the tune—that’s never the game we’re playing. [Because] what I notice is, anyone can get into the thing I was talking about before. They pick up on the visceral communication between the trio, and between us and them.

Right, but as an improvising artist you have an unusual hill to climb: to involve listeners in your mostly abstract pursuit. How do you bring people into that?

Most of the audience, they’re not professionals. They maybe don’t recognize when we’re playing the melody from an original score and when we’re departing from it. A lot of people are surprised to learn that we’re playing on a form at all! They hear it as one endless meandering of notes. I never gear the performance so that people need to recognize the tune—that’s never the game we’re playing. [Because] what I notice is, anyone can get into the thing I was talking about before. They pick up on the visceral communication between the trio, and between us and them.

Are there ever times when that’s not enough?

It’s up to us as performers to be responsible for making sure there’s a good groove there. My rule number one of ethics as a performer is that you can never blame the audience for being a bad audience. You hear players say stuff like “They weren’t so good tonight.” C’mon! That’s not their job. They paid to come into the hall to see us. It then becomes our job to give them something that they can hold and enjoy. … I’ve made music that totally loses the audience sometimes. Not because I wanted to, but because I didn’t give ’em enough hooks, enough familiarity. That’s part of our job, and it’s one of the reasons I like to talk between tunes. Because it brings us down to earth together for a moment. I’ll tell a little bit about what we’re about to do, to get them oriented. Honestly, I like it when the audience gets what we’re doing.

Accessibility has never been a negative in the lexicon of Chick Corea. Though he’s pursued improvisational dissonance in provocative ways (see Circle, with Dave Holland and Anthony Braxton), the pianist and composer has also created profound yet easily relatable music in a head-spinning array of settings. Early on, Corea formed an agile, pathfinding trio, with drummer Roy Haynes and bassist Miroslav Vitous, for the classic Now He Sings, Now He Sobs.

After stints as a sideman with Mongo Santamaría and Blue Mitchell, he cultivated his own approach to Afro-Cuban improvisation, then wrote some of the most challenging sambas in history (see Light as a Feather), then explored flamenco and bolero and tango (My Spanish Heart). Corea was in the room when Miles Davis’ pioneering Bitches Brew happened, and went on to build a jazz-fusion juggernaut (Return to Forever) that, through several iterations, sold lots of records and influenced generations of musicians.

His catalog includes gorgeous Satie-like miniatures (Children’s Songs) and luminous duet records (Crystal Silencewith Gary Burton, CoreaHancock with Herbie Hancock, the underappreciated Orvieto with Stefano Bollani) and assorted jazz quartets and quintets.

Consider Corea’s activity just during 1972. That’s the year Crystal Silence was recorded, and the release year forPiano Improvisations Vol. 2, which had been recorded the year before. 1972 was also the year Corea recorded both Return to Forever’s self-titled debut and Light as a Feather—though the former album wasn’t released in the U.S. until 1975.

Every musician should have a year like you did in 1972.

I don’t go so much by the number of the year as the project. Like if you’re asking about that first Return to Forever, I know where that sits because it was in New York. That first one for ECM was the first thing we did as a group—we had no record company for it at the time. We’d been performing regularly, and all we did was go in and play our set down and that was the record. We took the tapes to Germany and Manfred [Eicher, the ECM founder] was in on the mix. Light as a Feather happened after that, and I think Crystal Silence was before the first Return to Forever. The records didn’t come out in the order they were recorded. … They’re all quite a stretch from each other.

You’ve said before that Return to Forever was like a 180 from Circle, an attempt to play music with a groove.

I had two tunes, “Some Time Ago” and “La Fiesta,” and I put a band together based on that. The first guy I bumped into was Stanley Clarke, we played a gig with Joe Henderson here in Philly … then I asked Joe Farrell, then Flora [Purim, the vocalist] came to a rehearsal and brought her husband Airto, who I had played with earlier in Miles’ band. Our first gig was at the Vanguard. I went to see [Vanguard owner] Max [Gordon] and told him I had a group he would like. He said “Well, I can pay you blah-blah, and you can open for Roy Haynes’ group this weekend.” So we played two nights and it was such a hit that he hired us again to do a week. At that point I was booking the gigs and me and Stanley were carrying the Fender Rhodes around.

Was the sound we know from Light as a Feather there from the beginning?

Yes. Stanley and me and Joe were steeped in Miles, Monk, Coltrane. But of course Airto was not, not so much. It was a mixture for sure—Airto brought that authentic feel, and then Stanley, being a rebel from day one, played those rhythms his own way, not like Brazilians played them. It just clicked.

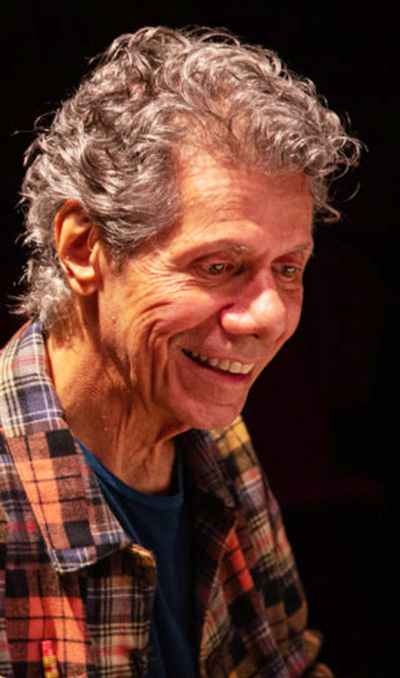

The cover of the Spanish Heart Band’s ambitious recent album, Antidote, shows Chick Corea in a flamenco dance position. One hand is above his head doing the finger-snap, the other is at his belt, possibly just post-snap. He’s smiling in a rascally sly way, like he’s just been caught doing something supremely un-legend-like and could not care less. It’s not a distinguished-elder look. It’s not a jazz look. It’s a “Lighten up! Come dance!” look.

The image speaks to a core truth of Corea’s approach to music: He comes at his work with genuine lightness. Even when the compositions are intricate and technically demanding, he’s running on impulse, not doctrine. Trying stuff. He can dispense musical heaviness in bulk, but he tends to offset the meta-conceptual with a rogue move or a comical quote.

Several times during our conversation, Corea uses the phrase “That’s not the game I’m playing” to draw distinctions between his philosophy and that of others. The distinctions themselves are important if sometimes small; his choice of that phrase is more significant, speaking to temperament, orientation, the priority he places on mental agility and flexibility. And, just as important, fun

At what point were you drawn to Afro-Cuban music?

In high school I had one fortunate gig with a Portuguese trumpet player named Phil Barbosa. He had a little quartet, and the conga player was Bill Fitch, who played with Cal Tjader later on. I knew nothing about Latin music. When we went to play the first time, I didn’t know what to do, and Bill showed me how to make a rhythm background on the piano, like the Latino guys. That was my beginning. And then he played me records—Tito Puente, Eddie Palmieri, Cachao, a whole bunch of people. That music and those rhythms just completely opened me up. It went straight to my heart. I was like, “I know this somehow. I’ve been here. I don’t know when or where. But this is really natural.”

Almost a déjà vu experience?

Exactly. It took what I had gotten into as a serious student of bebop and jazz and put it into a different frame—the openness within that music, the feeling of dancing and people having fun, really spoke to me.

Did you still consider yourself a student?

Absolutely. Of course. And then somebody recommended me for Mongo [Santamaría]’s band, that’s when I got a taste of the real Cuban tradition. Mongo was like a father. Real generous, and patient. Gave me just the right kind of instruction, showed me how to deal with rhythms that were new to me. It was the first time I encountered that kind of learning, and it’s a philosophy that’s stayed with me my whole life. If you want to learn how to do something, go find the guy who’s doing it. Ask questions. Take instructions from him. And then play the music.

Seems like you did that over and over your first years in New York.

When I got the gig with Blue Mitchell I was over the moon, because that’s the music I grew up with, sort of hard-bop rumba. I was basically stepping into Horace Silver’s band, and Horace was one of the megaheroes. I transcribed more Horace, particularly his tunes, more than any other transcription thing I did. … And the gigs [with Mitchell] were an adventure. We did two or three stints at Minton’s Playhouse, long stints like four to five weeks at a time, and six nights a week playing three or four sets a night. Me playing on a really shitty piano.

What was your experience of the social world of musicians in New York? Did people get what you were bringing musically right away?

I have no idea. I sorta had my head inside my coat then. I was just trying to find my heroes and play with them. … I’ll tell you one thing that happened that was really important to me. After Mongo’s band, Willie Bobo, who was the timbale player, formed his own Latin-jazz band and hired me. After the gig the first night, I was at the bar at Birdland having a drink. I think I might have been down on myself—feeling like I could have played better. It was just me at the bar, the end of the night. I notice this guy walking toward me. When he got close up I recognized him as Tommy Flanagan, and he just pointed at me and he said, “You got something fresh.” I was on cloud nine for two weeks.

He was an early adapter!

That was important for me because I always thought I was copying everybody. Because I was! I remember about six months after my first solo record Tones for Joan’s Bones came out, I found it in a record shop and bought it. Joe Farrell was on that—he was my elder by several years and I looked up to him. Anyway, I took it to his apartment and we made some peanut butter sandwiches and sat down and listened. And every time my piano solo came, he’d be listening to the piano solo. I’d play a lick and he’d go, “Horace.” Few seconds later, another like and he’d go, “Oh, Wynton [Kelly].” He was blowing me up because he was kinda right. I could hear what he was saying. That’s the view I had of what I was doing at that time.

For years now I’ve been wanting to thank Corea for sharing a small but significant detail about the making of Miles Davis’ Bitches Brew. We talked on the phone in 1998, for a Guitar World magazine story marking the album’s 30th anniversary. Everyone involved had vivid recollections of the sessions, but Corea dropped what was, for me, a mind-blowing factoid—that the sessions began, promptly, at 10 a.m. every day. I tell him that knowing about the timing became key to my understanding of the album, and that I’d brought it up in discussions around the 50th anniversary of the recording, which was earlier this year.

“That was made 50 years ago?” Corea asked, sounding genuinely stunned. “Jesus Christ.”

Has your perception of Bitches Brew changed over the years? I was struck by the energy of that “third” quintet on the Live in Europe 1969 set that came out a few years ago. The band with you, Dave Holland, Jack DeJohnette, and Wayne Shorter was really intense.

When we started recording [Bitches Brew], I saw it as a comedown from the live gigs that we were doing. They were really an adventure—just the wildest thing I had ever experienced up until that time. With Miles and his incredible melodic sense, and a laser intention that would set the scene for everything. And then the musicians in that band were just taking it every direction, imaginations were running wild in that band. So when we got in the studio to do Bitches Brew, I thought, “Oh, we’re making rock & roll now, Miles is doing some commercial music now.” Hahaha

Were you surprised by the editing?

When Bob Belden finally did the [2004] remix, I got interested. Before that I couldn’t tell what it was—it didn’t sound like what I remembered was happening in the studio. He put it back together again in a way that made sense. For one thing, finally you could hear keyboards. I thought, “Oh yeah, there it is! I knew I was in there somewhere.”

Corea has been averaging two new releases a year since his 70th birthday in 2011—a tear chronicled, in part, in the new documentary Chick Corea: Mind of a Master. Some of them have been elaborate projects: a three-CD live set of material from the trio with McBride and Blade, a large-ensemble reboot of the Spanish Heart concept, and so on. There are plans for a U.S. tour with the latter group, featuring Rubén Blades on vocals, in 2020, and that’s in addition to plans for another Akoustic Band record and more solo piano music.

His primary label in recent years has been Concord Records, which has issued significant works by Paul Simon, Santana, and many other established artists. Talking to label president John Burk, you get the sense that Corea presents his team with a unique air-traffic-control challenge: “He tours in three or four different configurations, and he’s out on the road a lot. Then he has a backlog of music ready to go that he wants to release. It’s taken us a while to line up the releases so they align with his touring activity, so that there’s a strategy that allows for each of the records to reach their maximum potential audience.”

Corea has no specific issue with the label; he says that Concord has been extraordinarily supportive. His beef is with the entire record industry. “I have forever disagreed with the commercial philosophy of ‘Don’t flood the market.’ My philosophy has always been, the more communication the better, the more records the better. I think we should capture ideas, document them, and put them out. Then the ones who are trying their best to market it go, ‘Oh no, not another one, we’re still trying to work on the last one.’ I understand that from the business point of view. I just can’t let that commercial reality affect the creative work.”

He mentions the trove of solo recordings he’s just begun to sort; another one is slated for release early next year. By then, he’ll be diving into an artist-in-residence appointment with the New York Philharmonic, and writing a concerto for longtime principal trombonist Joe Alessi. “It’s really exciting to me to write for orchestra—an entirely different beast. These projects, I’d really like to share them with the people who know me from the jazz stuff. … I guess to a label person I must look like a creature with eight heads or something.”

It seems like a gargantuan task to juggle so many endeavors in so many different realms of music. Most musicians just worry about the next gig.

And there’s nothing wrong with that. For me the most important thing is fun, being in musical situations like the trio, where we know it’s going to be a different challenge every time. Years ago I realized that I could have a million ideas and they might never get going without some structure. It’s only fun if I can give what’s needed. At this point in my life, the real way to get involved with any project is to book a commitment. So when Joe Alessi asked about the trombone concerto, I immediately [said], “Wow, yes, I’d love to do that.” And right away that turned into a schedule, and the need to deliver it at a certain time, and that meant planning.

Do you talk about this stuff in master classes, or interactions with young musicians? Seems like there’s a lot there that doesn’t get covered in music school—particularly that notion of having a vision and then prioritizing projects to support the vision.

The first thing I say is that doing anything in the arts requires some organization. It’s necessary. But I don’t focus too much on that. I more want to share my experience of being an artist, because when I’m at work I can see the result of what I do in front of my eyes, as I do it. That’s incredibly fulfilling, and not like most professions. Most people can’t tell how their effort is being received. I can see if I’m bringing people pleasure, if I’m inspiring anybody. When you do that, you’re putting something good into the world. I believe that.

On a vibrational level?

On many levels. What making music for people does, I’ve observed, is it stimulates what’s natural in all of us. It’s native sense, in every person. You don’t have to be a professional anything—all you need to do is be a living human being, and open to the play of imagination. Because imagination is everything … after you do this for a while, you see that you can use your imagination and imbue life with your creation. And that your happiness comes from what you imbue, what you bring of yourself.