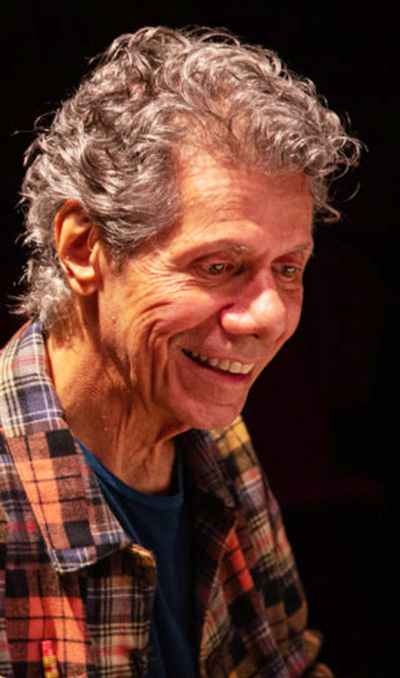

The Grammy-winning Chick Corea Trilogy performs Sunday night at Symphony Hall in Boston.

Ever since he first began plinking away at a piano at age 4, Chick Corea has loved making music. That’s carried him through a career that has seen him recognized as one of the most innovative and important figures in modern jazz, not to mention the most versatile. Just consider, for his 75th birthday celebration three years ago, Corea performed for six weeks straight at the legendary Blue Note in New York City, where he played in 20 of the different groups he’s been involved with over the years.

Corea released his latest album Oct. 4, the double-CD “Trilogy-2” on Concord Jazz, which, if we count correctly, marks his 99th album as a leader, not counting compilations. On Sunday, Oct. 20, Corea will lead the Trilogy-2 trio into Boston’s Symphony Hall for a concert that should include a lot of the music from the new disc and probably more than a few selections from Corea’s multi-decade career as pianist, composer and bandleader.

A Chelsea native, Corea veered away from his fascination with piano only a little with a side trip into playing drums at age 8. In his youth he was playing and soloing with the St. Rose Scarlet Lancers, a drum and bugle corps in Chelsea. He always preferred playing to studying, so the famous story goes he took off for New York after high school, spent about a month at Columbia University and about six months at Juilliard, before simply jumping into the Big Apple’s jazz scene.

Corea’s skill and adaptability soon had him playing with such jazz stars as Cab Calloway, Mongo Santamaria, Willie Bobo, Sarah Vaughan, Blue Mitchell, Herbie Mann and Stan Getz. The busy sideman released his own debut album in 1966, “Tones for Joan’s Bones.” But his profile really took off shortly after that when he joined Miles Davis’ group and went on to play on some of that master’s most significant records, including “Filles de Kilimanjaro,” “In A Silent Way” and “Bitches Brew.”

“Bitches Brew” had been one of the first records to be called jazz-rock fusion and as Corea had started playing the Fender Rhodes electric piano and routing it through several devices for extra effects, he was a key figure in that genre’s development. From 1971 to 1979 Corea helmed Return to Forever, a band originally designed to showcase his electric and acoustic playing with Latin flavors, but by their ’73 album “Hymn to the 7th Galaxy,” they were considered in the forefront of fusion. Starting in ’74 the most popular RTF lineup included Corea, bassist Stanley Clarke, drummer Lenny White, and then-19-year old guitar prodigy Al DiMeola.

After the RTF years, Corea spent the 1980s and ’90s playing in a wide variety of formats with many different jazz titans. Most of his works as leader involved his Elektric Band, with saxophonist Eric Marienthal, and his stripped down Akoustic Band, which tended to more trio work.

Since 2000, Corea has been exploring more classical music forms, melding them to his jazz sensibility and breaking new ground, as usual. One creative triumph came in 2006 when he was commissioned to compose a new piece to celebrate Mozart’s 250th birthday, for ceremonies in Vienna, and his “Concerto #2” was much acclaimed.

The Trilogy-2 band evolved out of another project Corea has led in recent years, his Five Peace Band, which includes guitarist John Mclaughlin and saxophonist Kenny Garrett. The rhythm section from that quintet forms the Trilogy trio, with Corea joined by bassist Christian McBride and drummer Brian Blades. McBride has performed with a long list of jazz icons from Freddie Hubbard to McCoy Tyner to Herbie Hancock, while Blades has backed everyone from jazz stars like Wayne Shorter to folks like Joni Mitchell and Bob Dylan.

The original Trilogy album, derived from a world tour of the trio, came out in 2014, a three-CD set that went on to win two Grammys, both for Best jazz Instrumental Album, and for Corea as Best Improvised Jazz Solo, for the tune “Fingerprints.”

This Trilogy-2 project also features live recordings from their recent world tour, with selections picked by Corea himself, and to no one’s surprise it’s a marvelously varied collection. There are standards like “How Deep Is the Ocean?” (in a stunning 12-minute treatment), and “But Beautiful,” a couple nods to a main Corea inspiration in Thelonious Monk’s “Crepuscule with Nellie” and the rare “Work.” Return to Forever fans will savor new renditions of 1972′s “500 Miles High” and “La Fiesta” from the first RTF album, while the Corea solo album chestnut from 1968 “Now He Sings, Now He Sobs” gets a vivid reworking.

There’s a cool surprise in Stevie Wonder’s “Pastime Paradise,” and it turns out Wonder was an early fan who used to sneak into the Bitter End to hear Corea back in the ’60s. And Corea and the trio do some of his famous former cohorts’ works too, with Miles Davis’ “All Blues,” and Joe Henderson’s “Serenity.” There’s a nice local Boston element to Kenny Dorham’s “Lotus Blossom,” which concludes the new record, as Corea said it brought back fond memories of his playing with Dorham’s quartet at Boston’s old Jazz Workshop with Henderson and Reggie Workman.

So with all of that as background and all those reasons to salute Corea on his return to Beantown, we were able to do a brief email interview with him.

Q: I’m sure you always enjoy returning to the Boston area and it’s abundance of music fans and musicians. But does a concert like this at Symphony Hall really have added resonance as it seems to reflect your whole career? The venue is not far from the site of the old Jazz Workshop/Paul’s Mall, where you played and heard some fine music in your early days. And it’s a couple blocks down from Berklee College of Music, which recognized you as a groundbreaking innovator in jazz with an honorary doctorate a few years ago. And finally of course, the venue is the bastion of “serious” music in Boston, reflecting how you’ve been acclaimed as a composer and performer whose music transcends boundaries. It must be very gratifying?

A: I’m impressed that you’ve made these connections regarding me coming to play at Symphony Hall. Yes you’re right about it being very special. My history with this beautiful and venerated old hall is a bit strange. I still have some regret at not having taken more advantage of the great music that must have been presented at Symphony Hall during the years I was growing up in Chelsea. In fact, my love for classical music only began midway through high school. I was so immersed in the music of Charlie Parker, Dizzy Gillespie, Monk, Bud, Horace and then Miles that I didn’t spend much time with the classical music until I left the Boston area and moved to New York.

Oddly, my first time inside the great Boston hall was when I performed there in some sort of festival concert. I remember a put-together quintet with Dizzy Gillespie, Mike Brecker and Steve Gadd. But that was a memorable and exciting night for me. It must’ve been some time in the early 80′s.

Q: You’re known for playing and writing for many formats and seeking out new collaborators. Is that perhaps a lesson for other musicians, that the difficulty of meshing and adapting to all these various formats is a key to keeping a fresh outlook? In other words, the challenge is the fun and you should relish the interplay and the quest to make it all work?

A: I just love to make music in any form. I’m lucky to have such great friends to create with. They inspire me and I continue to learn from them every time we do a new project.

Q: Just bouncing off that last question, if there is ever a time, in a project or collaboration, or in a smaller view just a tune in concert, when it is not working or just not landing well with the audience, what do you do? Your kind of fearless exploration brings the risk of something just falling flat and how do you deal with that, or try to avoid that?

A: Each night when I return “home” (that’s my hotel room) after the gig, always on the top of my mind is what didn’t work so well, as well as what worked very well. I make a mental note of what worked well and then do something to correct what didn’t. I carry a little Yamaha P-45 digital piano with me that I set up in each hotel room to practice and compose. When I sit down at it, I work on what I stumbled over the night before or how to correct the set somehow.

Q: By this time you have a pretty substantial history with this trio. Aside from their obvious skills, what attracted you to Brian and Christian as potential bandmates? All three of you could probably choose whatever or whoever you wanted to play with, but what makes these personalities such a vital force when you’re together onstage?

A: This one is hard to answer as it’s hard to find words to explain. There’s just such a great amount of affinity and musical realities that we all three share that, when the music happens, it all just flies so easily with little or no instructions or rehearsal. It’s just pure joy making music with Brian and Christian.

Q: In your younger years, your music as a composer and playing with Miles, Return to Forever, and others played a role in creating jazz fusion and helping the music cross over to rock and pop fans. We don’t hear much talk of that these days, but I’ve felt for example, that the Dave Matthews Band at its height was really playing a lot of jazz-type music, and now groups like the Tedeschi Trucks Band are also presenting improvisational and exploratory music under the guise of rock. I know you hate categorization, but how do you feel about the idea that jazz and jazz concepts are still crossing over, permeating many other styles, and just not being called jazz?

A: Well I find it difficult to discuss music using the names of genres and categories. With another approach at it though, I do observe that the use of improvisation in making music takes a certain skill and produces certain effects which, when done well and convincingly, please the musicians doing the improvisation as well as the audience. Maybe it has taken this long for the message of “jazz” and improvised music to reach more broadly – especially now with the internet. I do believe that every musician, no matter the type of music he or she makes, likes the idea of being able to improvise. Improvising uses our greatest resource: our own imagination.

I think it can be sensed by all involved when the performer is fully engaged and when his musical choices are more spontaneous – where there’s some risk, some adventure – trying something that hasn’t been tried before – “going out on a limb” – and so forth. When you can make a swan dive into the unknown and be graceful and easy about it – not worrying about falling down and breaking your neck, I think that makes life a bit more interesting and exciting.